The ascent of RIM as the manufacturer of the world's number-one brand of wireless email device reveals much about the set of social conditions in which the company and technology developed. Sturken (2004) argues that "technologies, in particular communication technologies, have been central to definitions of both modernity and postmodernity…these technologies did not create the modern condition, rather they emerged from the changing set of social imperatives and relations that constituted this condition" (p.72). While maintaining a social perspective, Chapter Two is a corporate history of RIM and will play a vital role in contextualizing the technology and this company in the proceeding analysis.

This chapter examines the interactions RIM has had with the institutions that have been pivotal to its development, from federal funding it received from the Government of Canada as part of a national innovation strategy, to a high-profile IP infringement lawsuit with a small patent holding company in Virginia. The chapter begins with some basic information on what the BlackBerry is, including: a description of how it looks, an explanation of its precise function, a product timeline from the device's first incarnation as a PDA with wireless capability to its current smartphone form, a description of the technology the device uses, and an outline of the technological developments that have shaped the device as it has evolved. This chapter provides the background Sturken and Thomas (2004) advocate in the introduction of Technological Visions, when they write, "situating discourses of technology within history…is a fundamental strategy in examining [technology's] social impact" (p.6). A corporate history of RIM should also be of interest to Canadian media and business scholars alike as a case study of one of the country's most successful international companies and brands (Harris, 2006).

RIM is one of the leading companies in the multi-billion dollar mobile email industry, enjoying the industry's highest market share at 19.8% in 2006 (Gartner Dataquest, 2007).3 In fiscal year 2006 (ending in February), RIM had more than 4,700 employees and revenues in excess of $2 billion (CND) that are driven by the company's near exponential subscriber-base growth (RIM, 2006 Annual Report, p.8). It took RIM five years to gain a million users (1999 to 2004), but the company hit its stride in 2004 and went on to more than double its subscriber base, up to 2.5 million in 2005 (Phillips, 2005). Significant gains were made in the international market in 2005 with half a million new users coming from outside North America. This meteoric growth continued in 2006, when RIM again more than doubled its subscriber base to 4.9 million by the end of the fiscal year. The seven months following the end of the fiscal year in February 2006 saw yet another doubling of subscribers, reaching 6.2 million global subscribers by September. Projections suggest there will be 123 million people using mobile email by 2009 (Malykhina, 2005), and based on RIM's leading market position, the industry's growth will likely continue to fuel the demand for BlackBerrys on a corresponding scale.

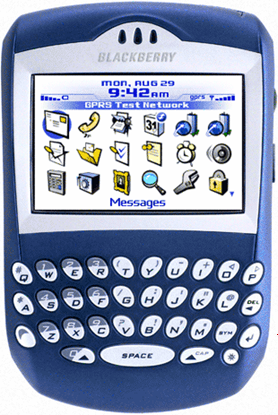

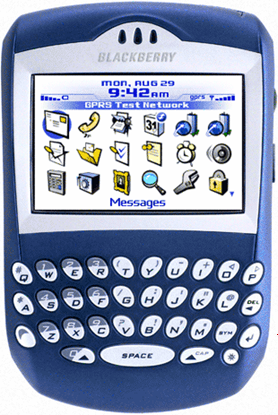

The BlackBerry is a handheld device whose primary function is to receive and send emails. The device is rectangular, with a screen on the upper half and a small keyboard on the bottom half. The QWERTY keyboard (the acronym represents the way the keys are physically laid out on a keyboard or pad) is specially designed to be typed on with both thumbs, which RIM Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Michael Lazaridis discovered was a quicker way of typing. Below are approximately life-like sized pictures of the BlackBerry and Pearl.

The BlackBerry started out as a two-way radio pager called the Inter@ctive Pager in the research labs of RIM in 1996. The pager was the fist pocket-sized two-way messaging pager and the predecessor to the BlackBerry. When the first BlackBerry was released to market in 1998 it could send and receive email messages as well as permit wireless access to contact and calendar information. BlackBerrys have continued to gain functionality over the years, with the first phone-capable device introduced in 2004 on the BlackBerry 7100t (Phillips, 2005). In addition to email, text messaging, and personal information management, all BlackBerrys now have phone capability and web-browsing function as standard features. The Pearl was launched in September 2006, designed specifically for the mass consumer market. In addition to having most of the BlackBerry's functions, the Pearl includes a digital camera and audio and visual playback (MP3 and video player), as well as BlackBerry Maps and voice-activated dialing. These features, along with email capabilities and an appealing design come together to create an alluring product that has proven to be increasingly successful.

Researchers at RIM realized when investigating paging technology that messages could be sent two ways on a wireless pager network, eventually leading to the development of the BlackBerry with its unique "push technology." Push technology allows emails to automatically show up on the device without the lag time of having to refresh a web-browser to view new emails. Towers et al. (2005) write, "[The BlackBerry's] small size and unobtrusive nature make it easy to take anywhere, and its functionality of checking email is an important one" (p.16). The ability to receive email messages on a BlackBerry serves as one of the main differentiating points that make it preferable to a regular mobile phone. According to a study done by Towers et al. (2005), most respondents said having a BlackBerry reduced their reliance on mobile phones (p.10). In fact, RIM promotes the BlackBerry as serving as a replacement for a laptop, and for mobile professionals who frequently travel, the thought of carrying a pocket-sized BlackBerry over hauling around a laptop, could be a highly appealing idea.

The BlackBerry's unique features extend to its design. RIM designed and patented the now ubiquitous QWERTY keyboard. The design allows for a compressed keyboard with each key doubling or tripling up in function and is part of the formula that makes the BlackBerry so popular: quick typing with the thumbs (Reuters, 2006). Ironically, considering the major litigation RIM went through in 2006, the QWERTY keyboard was patented by RIM but licensed to their competitors in 2002 so they could make some money off the popular design instead of making a costly contestation of the patents in court (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). Typing out emails with one's thumbs has resulted in a new office behaviour that has been dubbed "The BlackBerry Prayer." BlackBerry users, tapping out messages on devices held in their laps during meetings, look as though they are praying as they sit with their hands folded in their laps and their cast downward in contemplation. The keyboard design is also the reason the BlackBerry is thusly named. A marketing firm used by Apple had suggested the first BlackBerry be called a Strawberry because the tiny keys reminded people of seeds on a fruit. However, according to an article that appeared in The Globe and Mail, the term "Strawberry" wasn't a macho enough name for Mr. Lazaridis, and he opted for BlackBerry (McKenna et al., 2006).

Ken Belson from The New York Times writes "BlackBerry fanatics shudder at the thought of having to find a backup. Many say the keys, dials and software on the handsets are easier to use than those on rival machines like the Treo" (2005). RIM's primary competitors are the Palm Treo, Nokia, Motorola, Hewlett-Packard, and Samsung (Avery, 2006, Rivals at the ready), but RIM maintains a self-proclaimed "best-in-class" reputation and maintains the enviable title of being the "first-mover" in the industry (Finlay, 2002). The BlackBerry Pearl was designed to compete specifically with the Palm Treo (Business Week, 2006).

Mark Guibert, RIM's Vice President of Corporate Marketing believes that RIM is not in the position of directly competing with other handheld email devices; he claims that the company's business model is unique enough to maintain and grow its market-share. Guibert says, "As the world converges, there will be increasing alternatives from phone companies and handheld manufacturers. But because of the way we've brought BlackBerry to market - as a whole solution, with servers, handhelds, software and service - it's very difficult to compare ourselves directly" (Finlay, 2002). Guibert's comments were made long before the launch of the Pearl but are nevertheless still applicable. The Pearl has been brought to market in a way that appeals to a mass market consumer, but instead of providing server solutions the company is pursuing partnerships such as the recently announced agreement with Gameloft to develop videogames that can be downloaded and played on the BlackBerry (Flynn, 2007).

RIM has taken a unique approach in marketing the BlackBerry. Alan Middleton, a marketing professor at York University, calls RIM's marketing "brilliant" (Harris, 2006). According to Middleton, RIM's strategy has been to leave the telecommunications partners to handle the local marketing. "Instead of having to learn about each global market, they're using the people who have the deepest level of market knowledge to do it for them" says Middleton. By off-loading the burden of marketing and selling the product, RIM is free to focus on research and development.

Service for BlackBerrys run over the networks of telecommunication carriers, "a combination of RIM's network operations center and the wireless networks of the Company's carrier partners" (RIM, 2006 Annual Report, p.8). RIM lobbied Rogers Cantel for a number of years to upgrade their networks to a level where they could carry the data-intensive BlackBerry service (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). Rogers eventually agreed and was one of the two first companies to sign a carrier deal with RIM in 1998, along with Bell South in the United States. Today, T-Mobile is the largest carrier of BlackBerry service. The device itself costs anywhere between $150-$500, but that price pales in comparison to the data costs and airtime charges, of which RIM takes a share (Sibley, 2006). RIM will create enterprise-specific applications for large contracts, for example, creating applications that allow mobile professionals using the device out of the office to access internal applications such as the company intranet, email, and content-management systems for sales. The Enterprise Solution is appealing for companies not only because of the service it offers, but also because the data runs over RIM's network which saves the subscribing company's bandwidth thereby reducing its telecommunication costs, compared to mobile employees dialing in and accessing the data over the company's networks. These services come at a cost; access to the BlackBerry Enterprise Server (4.1) starts at $2,999, and $1,099 for the Small Business Edition. There are no alternatives, only poor substitutes, those being cell phones or external laptops. No other device provides the enterprise-focused services that RIM provides, hence the enormous popularity of the BlackBerry in the business community.

When RIM first launched the BlackBerry they strategically positioned the device as a tool for business. The company "educated" influential professionals about the product by giving away thousands of the devices for free to well-connected and high-profile professionals, including journalists, lawyers, political aides, and members of the U.S. Congress (McKenna et al., 2006). The move to create the BlackBerry as a must-have tool for publicly and politically influential people in the U.S. government and media had fortuitous results during the lawsuit RIM would later be involved with in the U.S. The effects of this placement will be discussed in more detail later in the lawsuit section of this thesis. The importance of the acceptance of the BlackBerry by the corporate market cannot be overstated. Guibert acknowledged this in an AP interview in which he said "BlackBerry's early corporate adopters helped push the acceptance of the product to a much broader market" (Phillips, 2006).

The market for the BlackBerry is differentiated based on who is making the purchasing decision. As described in RIM's 2006 Annual Report, the company is focused on three markets: Consumer, Prosumer, and Corporate (RIM, 2006 Annual Report, p.11). The Consumer purchases the device for personal use, the Prosumer purchases the device for a mix of business and personal use, and in the Corporate market the device is purchased by a company for deployment to its employees. In their 2006 Annual Report, RIM said it was not specifically targeting the Consumer market, but was "focusing on the Corporate and Prosumer market, where we have established market leadership and a reputation for best-in-class products" (p.11). However, the Pearl, which was launched in September 2006, is targeted directly to the Consumer mobile phone market.

Mobile telephony was initially perceived as a tool for professional use but as its popularity grew researchers found that mobile phones were used for both work and social purposes, and that there was "a clear shift in work and personal communication in behavior settings" (Grant and Kiesler, 2002, p.129).According to Castells et al. (2006), people are increasingly sending and receiving personal calls in the work setting, and vice versa (p.91). RIM's move into the consumer market with the Pearl is significant. Projections show that global usage of mobile phones will reach one billion in 2007 (Sharma, 2006). In the U.S. market it is projected that by 2010, 98% of households will have mobile phones and over 76% will have camera phones (up from 76.3% and 13.8%, respectively, in 2004) (Reed Business Information, 2005). Considering that over a billion mobile phones were sold last year and that some analysts are predicting the business market is nearly saturated with BlackBerrys, the consumer mobile phone market represents significant growth opportunities for RIM.

The Pearl was designed with the consumer mobile phone market in mind. Guibert stated this explicitly when he said "The BlackBerry Pearl was designed to attract new customers that hadn't considered BlackBerry previously" (Flynn, 2007). RIM partnered with Gameloft in early 2007 to create a series of video games that can be downloaded and played on the Pearl. In an article reporting on the collaboration, the author highlights that "with the release of the Pearl, RIM modified the design of the BlackBerry to create a more consumer-friendly smartphone, with a sleeker form as well as a camera and MP3 player" (Flynn, 2007). The Pearl clearly represents an attempt to bring about a shift in demographics for the BlackBerry brand. With the BlackBerry popularized by professional users, RIM is well positioned to capitalize on the growth of the mobile phone industry with the launch of the Pearl.

RIM's status as a mobile manufacturer makes it part of what some have termed the "Third Screen" revolution - the third screen being the development of the mobile phone and its networks (the first two screens are the television and the computer). Johan Wall, CEO of Enea, a Swedish-based network service and solutions provider, describes the Third Screen as being:

...for cell phone users in the developed world, the Third Screen will represent the long-awaited final convergence of the TV, computer and phone into a single, globally integrated network that will allow information, communications, games and entertainment to be accessed seamlessly everywhere from the home office to the automobile to even the remotest places on the planet (2007).

Wall goes on to name the capabilities that will develop as the Third Screen continues to grow, which include: global communications (an expanded communications grid), global positioning, universal contact, audio and video (high-end mobiles already have this ability), and environmental monitoring (enabled through Global Positioning Satellite [GPS] data). An industry analyst group, IDC, has noted that "major players like RIM will continue to invest heavily in GPS devices and solutions" (Hickey, 2007). Wall makes the prediction that for most people, the Third Screen will become their "Primary Screen"; a refrain that will likely gain currency in the coming months and years.

Another recent development in mobility is Private Branch Exchange (PBX), which has been predicted to alter the way mobile technology is used. PBX is a technology that allows calls (usually for a business or organization) to be handled over a private network instead of over a carrier network. Calls come in over the carrier network, but then are transferred onto the organization's private network, reducing expensive mobile airtime/costs. PBX has been tagged by IDC as being the primary tech issue of 2007 - part of the fixed-mobile convergence trend. Stephen Drake, the mobile enterprise Program Director at IDC, has said that PBX call features on mobile devices will boost productivity as the program enables in-coming calls to ring at multiple locations at one time. For example, if a call isn't picked up at the desk phone it is forwarded to other numbers associated with that person, such as one's mobile and BlackBerry. Drake predicts that PBX will improve call quality and save "stacks of cash" by moving in-building calls off the costly cellular network (Hickey, 2007). Drake says, "Enterprises must remain vigilant, since many wireless players will hesitate to offer fixed-mobile convergence options because a loss of revenue could result." On May 7, 2007 RIM announced the "first integrated enterprise solution to enable the seamless convergence of a BlackBerry smartphone with an office desk phone" (RIM, 2007, RIM introduces BlackBerry mobile). RIM has once again positioned itself as an innovative, market-leader - and that - is a money-making enterprise. It would appear that RIM's development of convergence applications such as the PBX server and games and entertainment puts it on-trend in a dynamic market (the mobile application market will top $2 billion in 2007 [Hickey, 2007]).

The outlook for RIM is bright and that confidence is reflected in its 2006 Annual Report. In the Report, RIM outlines the major trends it believes are driving demand for wireless handhelds and services. The two most significant trends RIM identifies are the continuing spread of the internet in terms of availability and capability and the decreasing price of network fees (RIM, 2006 Annual Report, p.9-10). In addition to the proceeding trends, RIM identifies the following as other trends driving the demand for wireless:

While RIM views market conditions as the imperative for product development, this thesis argues that it is in fact the particular intersection of public and private lives - driven by the neoliberal trend toward convergence and blurred boundaries - that has created the environment in which a product like the Pearl emerges. Regardless of which view is taken it appears the release of the Pearl comes at an opportune time for RIM.

The story of RIM's phenomenal growth from a small business founded by two Ontario university students in 1984 to an international brand with more than six million subscribers spanning 60 countries with revenues in excess of two billion dollars (CND) per year, is unusual in Canada, a country with few global companies. RIM was founded by Mike Lazaridis and Douglas Fregin while they were still engineering students. The men were childhood friends who had tinkered with electronics and attended science fairs together (Gange, 2005). In 1985, Lazaridis was at the University of Waterloo and Douglas Fregin was at the University of Windsor; months short of graduation, Lazaridis dropped out to establish RIM as an electronics and computer-science consulting company with Fregin. One of the company's first projects was a $600,000 contract with General Motors factories to develop a wireless, networked video display system that displayed information on the assembly line machines (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005).

In 1988 RIM was working on wireless point-of-sale integration with another company's radios (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). Lazaridis believed RIM could build better radios than the ones they were working with and so the engineers at RIM began working on a device for internal use (BlackBerry co-creator a national, 2005). The research led to radio technology, which in turn led to specializing in paging technology and networks (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). The work with paging technology led to the realization that although the technology was designed for one-way communication, it was also possible to create a channel that would allow for two-way communication. The revelation that messages could be pushed two ways on a wireless channel is the base of the technology on which the BlackBerry would eventually be based. Lazaridis knew from using the device within the company that he and his researchers had stumbled on something that provided an "addictive experience" (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). These comments from Lazaridis are telling since issues of addictive BlackBerry use have now become a buzz-topic among the media and subject of academic research as the device has gained millions of users. BlackBerry "addiction" will be addressed in Chapter Four.

Today, Lazaridis remains the face of the company (literally: he appears in an American Express credit card ad campaign as a profiled personality) and serves as the Chief Technology Officer. Fregin is Vice President of Operations but keeps a notoriously low profile (Gange, 2005). The name most often associated with RIM in recent years, second only to Lazaridis, is that of CEO Jim Balsillie. Balsillie, a Harvard Masters of Business Administration (MBA) from Peterborough, Ontario, was recruited to the CEO position in 1992. By 1992 RIM had nearly a dozen employees and sales of about half a million dollars per year (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). Lazaridis knew his strengths were in engineering and that he needed to bring someone in to run the business end of the company. Balsillie came into the position fully committed to the company's success, demonstrated by a $250,000 investment he made in the firm by mortgaging his home and taking out a small business-development loan (Avery & Waldie, 2006).

Shortly after Balsillie became CEO he made the decision to focus on just one key area, which was wireless and the convergence of mobility and digital data. In an interview with Innovation Canada, Balsillie said "Our approach was to create very marketable products - something that could really solve problems today. We made the right bets…It's all about systematically improving yourself in a sector that you think is going to be important" (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). Historically, it usually takes a "long while" for the commercial viability of technologies to become obvious, as it takes both investors and the public time to discover what they use it for (Nye, 2006: 41). John Perry Barlow (2004) claims that it "takes a generation for anything really new to arise from an invention, because that's how long it takes for enough of the old and wary to die" (p.181). Nye (2006) elaborates on this thought by writing "People need time to understand fundamental inventions, which is why they spread slowly; in contrast, innovations are easier to understand and proliferate rapidly" (p.41). One could argue that RIM broke this mold as they set out with the specific intention of making a commercially viable technology. Barlow would likely argue that mobile phones and wireless email devices are merely innovative by-products of the radio and Internet, which were the true inventions. Yet, framing the BlackBerry as an innovation as opposed to an invention runs counter to much of the hyperbole surrounding the product and the wireless industry.

In contrast to the often reverential tone of media reports on RIM and the wireless industry, a large body of academic work exists that focuses on the social contexts of technological developments. Mackay and Gillespie (1992) provide an important caveat to keep in mind when considering the "exponential" growth of RIM, when they write that: "technologies are created not by lone inventors or geniuses working in a social vacuum, but by a combination of social forces and processes" (p.688). Sturken (2004) writes about the complex and changing set of social imperatives and relations from which technologies emerge (p.72). She claims that the language contemporary media and popular culture use to talk about technology characterizes and defines and constructs them. In the introductory chapter of a reader titled Technological Visions: The Hopes and Fears That Shape New Technologies, Sturken and Thomas (2004) claim that all new technologies are described through metaphor as comparisons to the past and are the only way we have to talk about the future - that metaphors are constitutive and determine how the technologies are used, understood, imagined, and the impact they have on society (p.7). In a later chapter of the same reader, Sturken (2004) argues that representations of technology and the rhetoric used to define it are key to how technologies are integrated into social lives.

For example, Jonathan Sterne (2001) has written about the development of the stethoscope and asserts that the device was developed "as a technical response to a social problem in a clinical setting" (p.116). In the early years of medicine doctors practicing in public offices were dealing with the poor and in order for the doctors to position themselves as a separate social class they needed to physically remove themselves from the patient's body. Prior to the development of the stethoscope doctors would place their head to the patients body to listen for symptoms. The social conditions in which technologies emerge are important to consider when examining a technology's potential and limitations. This chapter strives to include a social perspective while reporting on some of the more technical aspects of RIM and the BlackBerry.

RIM got off the ground with a combination of personal investments from its founders as well as significant funding from the federal government (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). Lazaridis and Fregin launched the early BlackBerry in 1988 with a loan from the Government of Ontario New Ventures program and matching funding provided by Lazaridis' parents. When Balsillie joined RIM in 1992 he made a personal investment of $250,000 in the company. In 1994 the company received a $100,000 contribution from the federal Industrial Research Assistance Program, facilitated by Lazaridis' University of Waterloo connections. The Business Development Bank of Canada and the Innovations Ontario Program lent the company nearly $300,000. Both Lazaridis and Balsillie negotiated private funding from companies - Lazaridis secured a $300,000 investment from Ericsson (a mobile phone company) and Balsillie attracted almost $2 million in financing from COM DEV, a local technology company based in Waterloo.

RIM went public in 1996 and raised $36 million in a special warrant - which is similar to an Initial Public Offering (IPO), but occurs privately - the largest technology special warrant at the time. The company raised an additional $115 million the following year when it was listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange in 1997. The millions of dollars that were raised in the 1997 IPO-offering didn't preclude further government assistance. In 1998 RIM received $5.7 million from Industry Canada's Technology Partnerships Canada. This money was lent to help further the government's agenda to establish Canada as a global technology center, and to assist RIM in developing the next generation of mobile email handhelds. The loan was repayable out of future profits. Sometime before 1998 the Ontario government awarded $4.7 million from the Ontario Technology Fund.

When RIM listed on the NASDAQ in 1999 it brought in $250 million, and $900 million worth of shares were listed in November 2000. RIM's success was further rewarded by the Canadian government with an additional $33.9 million in 2000 from Industry Canada's Technology Partnerships. The Innovation Strategy website announces that RIM has benefited from the Government of Canada's Scientific Research and Experimental Development investment tax credits, which amounted to nearly a $12 million savings in 2002 alone (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005).

According to Innovation Strategy Canada, the federal and provincial governments of Canada lent and/or awarded RIM approximately $50 million from 1994 to 2000. While the government was loaning and awarding RIM money, RIM was returning the favors in kind, awarding money to their founder's alma mater to help fund research that could be beneficial to their business. An article from an organization dedicated to promoting technology businesses in Ontario, boasts that "RIM executives are directing big chunks of their formidable fortunes toward projects in fostering innovation, improving education and seeking to make government more responsive" (BlackBerry co-creator a national, 2005).

In 2002 the Canadian government established an innovation strategy to "pursue a vigorous effort to fund research and innovation…aiming to move Canada to the front ranks of the world's most innovative countries" (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). The federal agenda to "make essential research and technological expertise available to firms of all sizes, and to facilitate access to venture capital financing" can only be a happy coincidence for RIM in its early stages. The Innovation Canada website enthusiastically lists the number and amount of grants and funding the company has received, presumably to demonstrate the success the program enables. While the program has awarded millions since its inception, the amount of funding RIM has received has been returned many times over in the form of donations to universities and the establishment of a large Canadian think-tank. The company's most significant donation to date is a $100 million commitment to found the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics think-tank in Waterloo, matched by an additional $10 million each from both Fregin and Balsillie (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). The institute began research in 2001 and is now home to 60 scholars (Perimeter Institute, 2006). In 1996 RIM donated $439,000 to the University of Waterloo for a project that was to "develop the next generation of microchips for wireless communications." That project also received $285,000 from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). Lazaridis was quoted at the time, saying "This collaborative research program between NSERC, UW and RIM will develop low-power communications technologies that will be instrumental in furthering Canada's lead in wireless data communications (emphasis added)" (University of Waterloo, 1996). RIM's objective conveniently dovetails with that of the federal government's in terms of establishing Canada as a technology center.

Balsillie also donated another $20 million to establish the Centre for International Governance Innovation in Waterloo. John English, a former Member of Parliament (MP) and professor of history and political science at the University of Waterloo, serves as the executive director of this institute. Balsillie and English met in the late 1990s when English was an MP for Kitchener and Balsillie wanted to have Prime Minister Jean Chrétien appear at a meeting in South Korea for the signing of a deal with a local phone company. Balsillie lived on the same street as English and often walked his dog past his house. In an interview with Innovation Strategy, English said "He bothered me to death about getting a meeting with the Prime Minister on one of the Canada missions to South Korea. I talked to the Prime Minister's Office and I think it happened" (Case 7. Research in Motion, 2005). For RIM, business partnerships and support - as is so often the case - are a result of personal relationships.

The demand for BlackBerry has brought thousands of jobs to the Waterloo area, many for local graduates, and the investment in local universities has undoubtedly improved the facilities and research possibilities. RIM's location in Waterloo puts it in close proximity to several universities, where the company has access to a wide talent pool. Each year the company takes up to 400 students in co-op and internship placements. The donations directed toward research areas related to RIM's business agenda will most likely have the intended effect of driving significant amounts of the area's talent toward RIM's interests. The sometimes close relationship between universities and corporations is not addressed in this thesis, though the donations do beg the question as to how involved corporations should be in shaping academic research agendas.

While RIM was clearly doing very well financially by the late 1990s, as demonstrated by the sizable donations it made to local universities and think tanks, they were about to run in to some very serious trouble from a small patent holding company in Virginia.

From 2001 to 2006, RIM was involved in a lawsuit with a patent-holding company called New Technology Products (NTP), based in Virginia. What started off as a licensing issue that could have been resolved for a couple of million dollars turned into a five-year epic that finally concluded with a $612.5 million (USD) settlement. The settlement was made only after several appeals and the imminent threat of a ruling that was likely going to enforce an injunction against the BlackBerry that would shut down its U.S.-based business, which accounted for roughly 70 per cent of its revenues (Avery & Waldie, 2006).

An article in The Globe & Mail titled "Patently Absurd" - written during the height of the lawsuit - captures in great detail the convoluted five year history of the lawsuit. By 2001 the BlackBerry had moved beyond a status symbol for only the jet-setting corporate executive (Phillips, 2006) and had become a "must-have" tool for a broader stripe of executive, especially among lawyers and politicians (McKenna et al.: 2006). In May of 2001 a small article appeared in The Wall Street Journal under "Pager Maker Gets Patent for Email Delivery" after RIM had successfully sued a competitor for patent infringement. The article was read by Donald Stout, a lawyer in Arlington, VA, who represented Thomas Campana Jr. of NTP. Campana was an inventor who had bought dozens of patents for a system to send text messages from computers to wireless devices nearly a decade earlier.

In the early 1980s Campana formed a company called Electronic Services Associates (ESA) and developed a paging system that used radio waves which enabled the system to be used nationally instead of being confined within cities. He patented this device with ESA. In 1985 Campana helped start another company called Telefind Corporation, and had ESA act as its engineering arm. The two companies made many more developments to the paging system, but after a failed bid to partner with AT&T in 1990, the company went bankrupt in 1991. However, Campana left the partnership having bought the rights to dozens of patents related to the wireless paging technology.

Douglas Stout was a patent lawyer who had spent four years working at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office before opening his own practice. Stout heard about Telefind from a lawyer friend and he approached Campana to create a patent holding company. In 1992 the two men formed New Technologies Products (NTP). The company was formed with the sole purpose of one day suing a company that infringed on its patents. Stout describes the formation of NTP as never being about making or selling things: "It was about protecting potentially valuable ideas" (McKenna et al.: 2006).

It seems appropriate here to cite Nye's (2006) observation that "the patent system had been designed to encourage innovation, but corporations discovered they could also use it to dominate markets. During the twentieth century, as research laboratories largely replaced the private inventor, technologies were selected less by voters or consumers than by managers and investors" (p.137). In this case, the technology was nearly taken off the market due to the actions of a man who purchased patents with the sole and malicious intent of holding onto them until a company to sue could be found.

Between 1992 and 2000 nothing happened with the patents, but by 2000 wireless technology was becoming increasingly pervasive and in that year Stout believed the time had arrived to exercise the patents and sent out a form letter to several companies, including RIM, warning them that they were infringing on wireless email patents. The letter invited the companies to negotiate a licensing agreement with NTP. During the trial RIM said it conducted an internal review and concluded that it was not infringing on any patents, but could not produce evidence that they had responded to NTP's letter. The Globe and Mail article quotes Stout as saying, "In the world of patents, you're not going to get any traction unless you're willing to enforce them" (McKenna et al., 2006). When Stout read the Wall Street Journal article in 2001 he knew NTP had found a company to enforce its patent against. In the world of patents, a patent is only good (or valuable) if it is enforced.

In November 2001, NTP filed an infringement case in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. RIM refused to settle and released a news release that called the claim unsubstantiated (McKenna et al., 2006). This was just the beginning of a series of choices when RIM refused to settle, which only escalated the suit's eventual settlement. RIM seemed convinced that NTP's claims were invalid because by the time NTP filed its patents the technology was already being widely used by RIM and other companies (McKenna et al., 2006). The case first went to trial November 4, 2002, but far from proving their case, RIM's lawyers hung themselves with their own rope:

To prove that the technology had been used prior to 1991, RIM's lawyer did a demonstration, sending a message from a computer to a pager, with technology that had been developed by David Keeney in 1987. However, to make the demonstration work RIM had swapped in a newer version of software. The NTP lawyer spotted this difference and called them on it during cross examination. They judge told the jury to disregard the demonstration, which was a turning point in the case, because the judge told the jury that the defendant's key piece of evidence was fabricated (McKenna et al., 2006).

The jury found against RIM and the judge later awarded even higher damages to NTP than the initial ruling, based on RIM's "wilful" and "fraudulent" courtroom conduct. The total lawsuit award at this ruling was $240 million (USD); including $53 million (USD) in damages, a royalty fee of 8.55% on each BlackBerry sold in the U.S., and $4.5 million (USD) in legal fees (McKenna et al., 2006). RIM predictably refused to accept the ruling, fired its lawyers, and launched an appeal. The judge barred the sales of BlackBerrys in the U.S., but stayed the order when RIM put an equal amount into escrow while the lawsuit was appealed. In the meantime, Thomas Campana Jr. died in June 2004. The case was now being moved forward by his father, Campana Sr., and Douglas Stout.

RIM's new lawyers urged them to settle and in March 2005 the company was close to settling with NTP for $450 million (USD), but the deal fell apart in June 2005. Instead of making a better offer, RIM launched an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, which also failed. Not to be deterred by the courts, RIM got political:

Around the same time, RIM also mounted a major lobbying and public relations push in Washington. It was eager to convince policy makers that it was the victim of patent trolling gone wild and a dysfunctional patent system. It hired two Americans it knew well -- former ambassadors Mr. Giffin and Mr. Blanchard -- and their respective law firms to persuade members of Congress to save the BlackBerry (McKenna et al., 2006).

In addition to convincing members of Congress that RIM was being taken advantage of and that technology companies the world over were threatened by NTP's actions, Blanchard was also trying to speed up the review process in the hopes that a favorable ruling would come out that would influence the courts. The approach worked: soon the patent office was spitting out reviews in record time, calling into question the validity of NTP's patents and giving RIM its first bit of good news in years. RIM's reviews had jumped the queue at the notoriously apolitical patent office, surprising even experienced Washington intellectual property lawyers. Years of marketing the BlackBerry as an intensely personal communication device had worked: it had become engrained in the culture and work habits of the people running the world's richest and most powerful country. When RIM was threatened with an injunction, the response was that the BlackBerry was an integral component of the U.S. economy and vital to national security. McKenna et al. (2006) write:

RIM and its defenders in Congress played their trump card - invoking the spectre of another major terrorist attack in Washington. Several lawmakers, impressed that their own BlackBerrys had not failed on Sept. 11, 2001, while cell phones everywhere went dead, warned in hearings that shutting off the devices threatened national security. Even House Speaker Dennis Hastert - the top Republican in Congress and an avid BlackBerry user - intervened on RIM's behalf.

In another article, Susan Drecker (2006), highlights RIM's court statements that include testimonials from a former Homeland Security official who said the BlackBerry worked after Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast when cell phones didn't, and the head of the New England health group saying that the BlackBerry is part of its plan for a response to an avian flu outbreak.

In early 2006, the court was about to rule on the infringement, and it looked as though the injunction was going to be upheld against RIM. However, the company had been buoyed by the U.S. Patents & Trademark Office (PTO). The PTO had twice previously rejected all of NTP's key patents, and in a final ruling from February 24, 2006, it once again rejected all of NTP's patents, allowing RIM to continue operations in the U.S. (RIM, 2006, RIM provides update on patent). RIM was ready to fight to the end, and on February 9th it released a statement that the company had developed a non-infringing workaround that would enable U.S. users to continue using their BlackBerrys uninterrupted (RIM, 2006, RIM announces workaround). At the last minute, shortly before a judgment on the infringement was due and a ruling against them looked inevitable despite the PTO rulings, RIM finally settled with NTP. The settlement was for $612.5 million (USD) U.S.

Rebecca Harris (2006) believes the lawsuit may have actually helped the brand, as RIM was in the news continuously during the height of the dispute. Political economist Robert Babe (1995) writes, "…communicatory power derives from and contributes to economic power" (p.72). For RIM, the lawsuit created a media profile and level of communicatory power that it would not have otherwise had. Especially beneficial were high-powered U.S. politicians who said that the national economy and security depended on being able to use the BlackBerry - a significant a journey from RIM's establishment by two university students in 1984 to being an integral part of the secure functioning of the world's most influential economy. Aside from the settlement, for which the company had budgeted, the lawsuit appears to have had only a nominal effect on RIM, with the company posting its highest subscriber growth and revenues in 2006.

RIM is a Canadian success story, one that is the result of a number of power plays during the company's more than two decades of business. From securing federal funding to making reciprocal investments, political maneuvering at home and in the U.S., RIM has made a series of well-timed moves that has enabled it to jockey to the lead position in a competitive, multi-billion dollar industry. An examination of RIM's history opens a window into the dealings that make and shape such emerging businesses. The actions of RIM and other information technology companies are sure to draw continued scrutiny as these companies negotiate policy and funding dynamics as the mobile communications industry grows.

The BlackBerry developed as the result of a particular set of social imperatives that coalesced within a neoliberal economy which contributed to the reflexive positioning of the BlackBerry as a tool of efficiency. RIM flourished alongside the Canadian federal government's desire to establish the nation as a global technology center beginning in the late-1990s, and received a heightened media profile during the IP-lawsuit which included U.S. government endorsement of the BlackBerry as an integral component of the country's economic and national security in a post-9/11 world. It is a combination of these factors that have played a role in RIM's propulsion to industry leader in the multi-billion dollar mobile communications space.

Sennett (2006) believes that "the new economy is still only a small part of the whole economy, but that it exerts a profound moral and normative force as a cutting-edge standard for how the larger economy should evolve" (p.4). This view of technology serves to reinforce this thesis' earlier claim about the significance of RIM's positioning of the Pearl as a work/life tool with the capability of improving productivity and efficiencies through connectivity in these areas. Turkle writes that "Technology does things for us, but also to us, to our ways of perceiving the world, to our relationships and sense of ourselves" (2004: 23). Turkle and Sennett's assertions about the influence of technology and new-economy discourses support this thesis' claim that RIM's vision of the role the BlackBerry plays in the personal and professional worlds carries implications for society outside of those who use BlackBerry's or view their advertisements. RIM's discourse contributes to the evolving definition and of the role technology plays in public and private life.

The BlackBerry and BlackBerry Pearl are cultural artifacts in the sense that they derive their meaning from societal designations; and as such, an examination of the language used to describe the products will provide further insight into the social imperatives that drive its development and adoption. The following chapter will be an examination of RIM's rhetorical strategies in its online promotion of the BlackBerry and BlackBerry Pearl.

3. Defining a PDA and smartphone is complicated; the cited Gartner data "excludes smartphones, such as Treo 750 and BlackBerry 8100 series, but includes cellular PDAs such as BlackBerry 8700 series."